Curator Lena Essling

KH: Most recently, we met at the opening of Marina Abramović’ retrospective The Cleaner, currently hosted by Moderna Museet, Stockholm. An exhibition of this magnitude and international significance seems like a very natural fit for Moderna Museet, in light of the museum’s long-standing commitment to Performance Art – a legacy that can be traced back to the museum’s formative years, and the vision of its first Director, Pontus Hultén. Was there a specific reason for hosting Marina Abramović’ at this particular moment in Moderna Museet’s history?

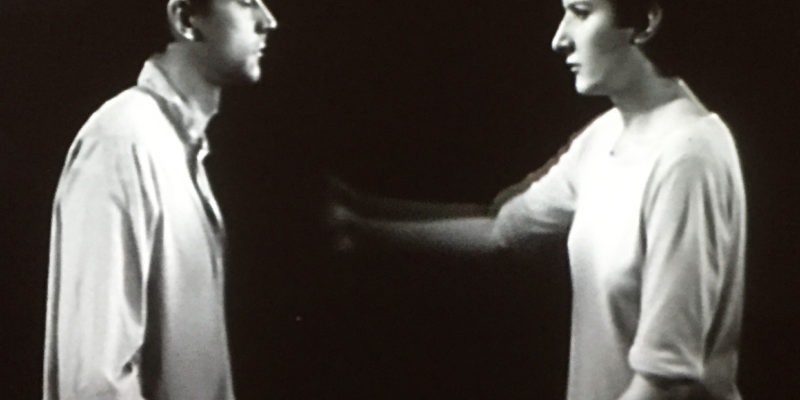

LE: Marina Abramović’s work in performance art is uncompromising from the very outset in the early 1970s, and over time, she has kept pushing the boundaries of her work – in effect changing the parameters and understanding of this practice altogether. So, this is an artist who has in part shaped where this art form stands now, as well as having influenced other fields of practice, not least via decades of teaching. There aren’t many artists of this magnitude in the field of performance, and the timing was right both for Marina and for us. This is the first European retrospective .

I wanted this exhibition to present the full span, as much as possible, of an artist who has devoted herself to this form of expression for several decades, but also to illuminate what is happening here and now in her work. It would be difficult to imagine a stronger catalyst than Marina Abramović for a discussion on the past and current status of performance art, even if this is naturally a field that develops in many different directions. At best, The Cleaner will energize and help give visibility to a form of expression between visual and performing art, which we are not always able to address on a larger scale in our galleries.

It has been important to us to manifest a number of solo exhibitions on women artists – not for the sake of statistics, but simply because they still needed doing in order to give a more comprehensive understanding of where we stand today. The story needs to be made more complex. To do so with an artist who has devoted herself to the time based, which as you say is part of the dna of this institution to begin with, makes it even more relevant.

KH: The majority of artworks we encounter today do not rely on audience participation for their completion, and yet there seems to be a revival of sorts at hand – a renewed interest in Performance Art. What role do institutions play in this revival and would you say there is a conscious shift in the programming of MM to accommodate more Performance?

LE: Yes, it is certainly a vital and diverse field today and I think we all wish we could contribute more. I think it is important for institutions to both mirror and partake in the development of new forms of art. Performance has been around for several decades, but many of these works still have a rather high threshold for general audiences.

It is important to give space and time for both new and historical works, in order to do justice to the essential role that live, participatory arts plays in dialogue with other forms of contemporary art – Just as most institutions recognize moving image as a central part of how art history has unfolded. In the case of this exhibition, it makes sense for it to be made by an institution that has the collection and memory base to support putting it all into context for audiences, apart from programming new performance works when we can.

KH: Would you say that Modern Museet’s commitment to performance art is primarily to ensure a balance and breadth in the Museum’s programming or is it also a strategy to attract new or different audiences?

LE: I would say both aspects are important to us. We strive to be inclusive in our programming, and to present what we find to be the most interesting expressions of art to all of the museum’s audiences, in an informed way. With Marina’s exhibition we have seen audiences here that don’t always find their way to the museum. At the same time, our core audiences are able to see this work up close and as something completely central, as opposed to work that is usually given a supporting role in presentations, due to the fact that it can be rather difficult to represent in the gallery.

KH: Is it the case that Performance Art attracts a noticeably different demographic than more static exhibitions and if so, what is the difference?

LE: We have seen a great variation of both visitors and writers get involved in this exhibition, some coming from backgrounds in performing arts of different kinds, but also from film, poetry, activism or music. In the case of Marina’s exhibition, she has a wide audience with ties to pop culture, but simultaneously – and what could be seen as the other end of the spectrum – an audience with great interest in inter-human relations, spirituality, and alternative life styles. That is probably true for other performing arts programs as well – They touch a different nerve, a live wire. This type of exhibition may not bring the huge crowds, but it reaches far beyond our core group of visitors.

KH: In recent years, there has been a lot of debate about increasing social isolation, due to our growing dependency on digital technology, both in workplaces and as a form of entertainment. Can Performance Art be used as a tool for re-engaging audiences who have become increasingly disconnected from the museum world or other forms of communal interaction?

LE: I suppose some forms of performance art would certainly do this, and could even use this is their subject matter. But in general, it could never be an instrument of change in and of itself. I think that an institution like Moderna Museet should strive to be a force in re-engaging outside of isolation, whether that isolation is digital, intellectual or otherwise. We hope to be an area of discussion, thought, learning and sometimes controversy – which comes with the territory. At the same time, many artists are continuing to work closely with technology, as they always have. Some are making work about this isolation, of conducting one’s life via avatars or chats, and others are finding completely different ways ahead, pioneering new usage of digital platforms. That is another strong part of the legacy of Moderna Museet – the merge of arts and technology.

KH: Marina Abramović speaks of Performance Art as remedy of sorts, providing audiences with a much-needed escape from fast-paced existences and social isolation. If Performance Art can be seen as a remedy for our collective social needs, does that give museums a therapeutic role in society?

LE: Yes, she sometimes speaks about her public participatory projects as safe zones; places or states of minds where we – audience, artist, facilitators – jointly have the possibility both of introspection and interaction, wordlessly sharing an experience of bewilderment and vulnerability with others. When we, as an institution, take it upon ourselves to offer that to the audience, we do so in mutual trust with the artist. Both parties want to truly put this idea to the test; what is the artist on to here? How can we accomplish something together as both monumental and fragile as this?

In Stockholm, Marina’s recent project at Eric Ericsson-hallen truly became a far-reaching community project where the diverse choirs made up an important part of the interface. Demographically, we are certainly only scratching the surface in terms of reflecting contemporary Swedish society in that one week. But I think both parties – institution and artist – were stunned in the end, by the richness of experiences, expressions and engagement so generously brought into the space, setting it all in motion.

KH: In the spirit of International Women’s Day and specifically with reference to Marina Abramović (one of the world’s most iconic female artists), I wanted to talk briefly about women in the arts.

When it comes to the representation of women artists in major art institutions, statistics confirm that female artists still make up less than five per cent of major permanent collections in North America & Europe. Thankfully, however, it would appear that many international institutions are actively addressing gender disparity in their collections & exhibitions. I know that in terms of collections, Moderna Museet has – at least in more recent years- placed female artists in focus through initiatives like The Museum of our Wishes. And, as far as exhibitions go, the last decade is testimony to the Museum’s commitment to venerating the practices of leading female artists, with exhibitions including Niki de Saint Falle, Tala Madani, Yoko Ono, Eva Hesse, Cindy Sherman, Hilma af Klint, Louise Bourgeois, and now, Marina Abramović – to mention a few.

Within an international institutional context, would you say that Moderna Museet is a Pioneer to a certain extent – A world-leader in giving strong representation to female artists?

LE: We do get a lot of recognition for this from others internationally, and just looking at the programming of many other institutions around Europe and the US we have certainly taken a different direction to most in that regard.

KH: In connection with that, how heavily do gender politics weigh in to the Museum’s prioritization of some exhibitions over others?

LE: It is one very important factor weighed in alongside countless others when names are discussed in our exhibitions meetings. Programming is truly complex, so much comes into play – but I would say that the first criteria for getting a name up for discussion is always the grade of urgency to show a specific work at a specific time – The passion to carry it out stems from there.